I lived with Kristine for two weeks in a brothel in Seville. She would often yell down at breakfast from the third floor mezzanine to ask how I liked her tomate, the crushed tomato and olive oil drizzle on toast that is a staple there. I always yelled that I loved it, and she would pull her head back contentedly. The pinch of coarse salt made it heavenly.

Two of her three kids were adopted, from Peru and Colombia. She doted most on Esmeralda. Kristine herself came from Denmark, and whenever she described her husband, who split his time there and with them, researching and teaching Spanish history, her voice shook. On my last night, she shared that though the house’s past had made it affordable when they first moved, they were now on the brink of collapse. Her eyes filled with tears as she speculated they might need to sell upon his next return and abandon Spain. Airbnb had been a last ditch effort to hold on.

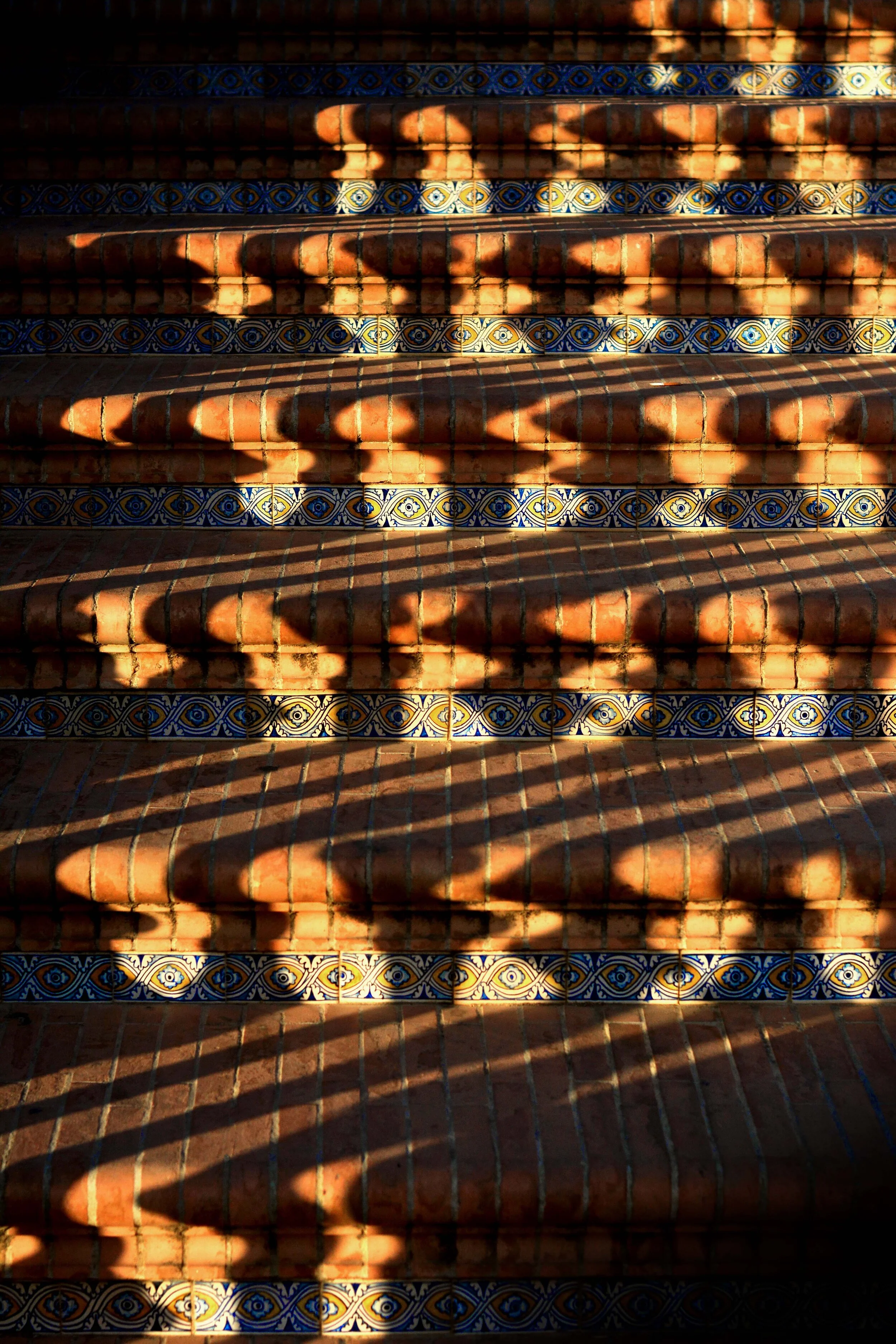

She said in a former life she had been a mosaicist, moving to Italy once in her twenties solely to study the art of assembling irregular and particolored stones into larger overall images, patterns, and statements. Her fingers grazed the blue and white azulejo tiles behind the stove as we cooked sopa de ajo, an art Arabs left that traveled even to Mexico.